Remnant House - Autumn 2023

A plane tree, like an ancient monster, has lifted the house by its foundations and split it crosswise. The front rooms are sharply tilted. Branches and tendrils fall in through the doorway and windows. The back remains more level. Small timber rooms filled with light and dust branching from the hallway, which descends to a low entrance with a concrete floor and exposed pipes climbing the walls. Outside is an orchard left to become a forest. Lemons and oranges fall through the kitchen window, small, sweet plums through several others. The room with the warmest aspect is screened by avocados and kiwifruit vines. The bricks in the courtyard are stained purple from a century of fallen mulberries.

Index

One

Remnant House

The house I grew up in, and only left well into my twenties, was a worker’s cottage, mysterious and decrepit, a palimpsest of all the successive families that had lived there. It had originally been built in the nineteentwenties by a family employed in the construction of the neighbouring capital, one of a row of three that used the same set of plans. (Our town had been there already threequarters of a century, long enough to have overflowed its elegant, Georgian grid layout, and formed pools and hidden channels up and down the length of the Old Road.)

Its art-deco stained glass windows and bulbshaped light fixtures had survived from that time into the present day. Its beige carpeting and pastel pink and green interior wallpanels, on the other hand, had crept in sometime in the nineteensixties or nineteenseventies. Likewise the sunroom, which had originally been the front porch before someone had put up the wooden scaffold around it and walled it in. And likewise the laundry at the other end, which along with the toilet had presumably been off in it own separate annexe. The shed though had made it through the century without even being repainted. It was a timber structure at the bottom of the yard, with great double barn doors that had rotted off their hinges and had to be fastened shut with rope, a bare earth floor covered in uneven masonite boards and a hanging loft in which possums and rats and cats fought for ownership.

My parents, on moving in, set about correcting the more dubious improvements, but in the process introduced new idiosyncracies all their own. They pulled up the carpeting to reveal the original floorboards which had turned (or had maybe always been) rich black and brown, speckled with decades of paint, filled with grooves and pits and cracks that left splinters in your feet. They chose not to repaint the pastel pink and green wallpanels, which had anyway acquired over the last few decades a gloomy patina. Instead, they hammered in timber boards over the top. The structure had settled and shifted, so that none of its corners met at a right angle anymore. The boards had to be shaved or cut short to fit the space. Nothing could be introduced into the house without undergoing some transformation.

The house had been sold as a fixerupper. There were always two or three renovations underway. There are still renovations underway. These didn’t follow any considered plan, but were adhoc, seasonal, aleatory and so liable to be leftoff halfdone if a spell of unfavourable weather lingered around too long. One year, the grand project was to paint the exterior brightwarm yellow with blue accents. A celebratory kind of mood carried us through the planning, the acquisition of supplies, the first brushstrokes, but stalled out around the threequarters mark. By the time we returned to the business of the exterior walls, our work had turned pale under several droughty summers, besides which manufacture of the original yellow had been discontinued. In the meantime though, the unfinished work had inspired one or two bright imitations, up and down the adjacent streets.

Being that it was a heritage building, there were ostensibly council restrictions on the type of improvements that we could make to it. That did not stop the holey redtin roof being replaced, the picket fence being torn down and tall blue colourbond being put up in its place, the chimney flue being boarded up and the garden allowed to ramify into a jungle of cocos palms and cypress and planetrees and plums with small tartsweet fruits, wisteria and ivy overtaking the rotted trellises, and in a rocky corner where nothing else could grow, a decorative quincebush that so anchored itself into the soil, that nothing short of total excavation will ever uproot it. Really, the council heritage restrictions were too late to rest the tides of change. The house would grow and contract following its own kind of logic regardless.

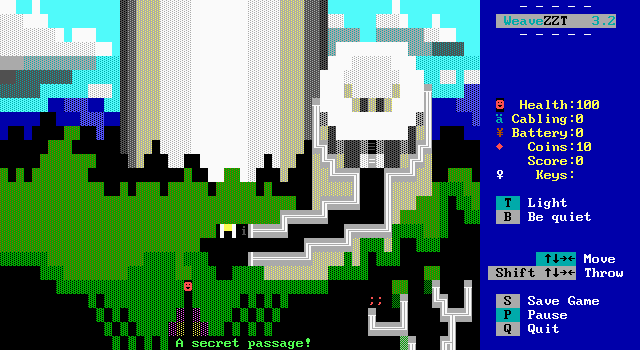

With things being boarded over, walled off, paths cleared and others left for the jungle to reclaim, mysterious hidden spaces were always appearing around the place. Reorganising the VHS tapes in one of the living room cupboards, I discovered a narrow halfheight passage, one you would have to crawl through, into the back of the kitchen fireplace. I discovered a wooden trapdoor in the greenhouse by the shed, buried under mulch and dirt and which opened into a shallow pit filled with more dirt. I climbed into the roofspace through a ceiling hatch and saw that up here was its own labyrinth of loadbearing beams and partitions, which in no way matched up to the configuration of rooms below.

I remember one summer, my preferred place to sit was in the front garden under the cedars and at a small iron table. The afternoon sunlight fell through the trees into this corner and a section of the street all the way up to the building that had once been a milkbar was visible from here, but the understorey was so screened off by fencing and ivy and the drooping cedar foliage that nobody passing on the footpath could see in. Sometime after that the undergrowth was cut back. I moved to the disused alleyway between our house and the neighbour’s, where decades ago several large white stone tiles had been laid down. Being screened off from the sun, it remained cool in summer. But the neighborhood cats peed there and it had a lingering ammonian scent. I didn’t remain there for long.

There were so many of these spaces around the house. I can halfremember, or maybe had dreamed, that there were others too. When very young, the area outside my bedroom window seemed overgrown like a rainforest, full of ferns and moist decayed soil, protected by green netting and trellises. It was infested with mosquitos and centipedes even during winter. But this is difficult to reconcile with the airy outdoor patio it has since become. I was for a time also sure there were hidden rooms which had been walled off, or had never been connected to the rest of the house in the first place. I dreamed about all sorts of landscapes starting just past the boundaries of the garden, behind the shed, like Siberia or Kamchatka or vast industrial works.

Looking through council records one afternoon for something else entirely, I came across our address and those of the other two houses up the street, and the description next to it, Remnant House. Not that the council of all people could have known, but it seemed an apt way to describe the place, by that point one hundred years old, transformed and decayed and overbuilt and threatening to collapse at multiple stresspoints, not least the plane tree in the front garden lifting that side of the house out of its foundations, but still full of people and cats, possums, lizards and birds, inhabiting all different rooms and hollows halfconnected to one another, a ruin in motion.

Two

Imaginary Videogames

A recurring dream I have sees me walking into a preowned games store and discovering a cache of things I had never known existed. The store is almost invariably structured as follows. One main room accessed from the street by a glass, swinging door, and filled with rows of racks and shelves lining the walls. Then, at the back of the store, a smaller room, similarly lined with shelves and filled with racks, but also, in several locked glass cabinets, cartridges and controllers and the obsoleted systems for playing them.

In my dreams, scanning through these cabinets, I find something I had never even heard of before, that I should have known about an obscure sequel, a spinoff, or something completely unknown, but with an interesting cover. Of course, the dream ends long before I have the chance to play any of these games; the focal point does not seem to be in playing them, but in discovering they exist, and imagining the worlds they contain.

I found copies of so many games in the real-life version of this store, growing up. Plenty of keystone titles and just as many lemons. Games are often more interesting as an imaginary thing than as something to actually play. When you look at screenshots and read walkthroughs and synopses, the thing you piece together may be richer and more interesting than what you end up playing.

For example, I knew about Earthbound for years before ever actually playing it. It was doubly inaccessible for me, being that it was never released in Australia and further that it was only on the Super Nintendo, which our family never owned, and which as such is where all imaginary and impossible games exist still for me. But following some initial lead first led me to screenshots, then to a walkthrough, which focused mainly on mechanics but then provided just enough information for me to reconstruct my own version of this game. Screenshots of bluefaced enemies and maps that reminded me of my own hometown. Descriptions of some evil influence originating from a faroff source. I imagined some sprawling opus that would somehow only grow in its scale and thematic scope the further inward you progressed.

It had not occured to me to simply emulate the game. But finally playing it years later, for all its merits, confirmed that yes it was ultimately like the other games of the era, that however anomalous its story and themes were for the time, you could still place it in a genealogy with other roleplaying games of the time, that it still had randomised turnbased combat and characters who could only say so much, and the same inherent boundaries as anything else that had to be fitted to a four megabyte cartridge.

Videogames depend on their players to hold two conflicting notions in mind. On the one hand, they need to articulate rules of play in such a way that their players can learn them and so access the game world. On the other hand, they also need to suggest that their game worlds in some way exceed the boundaries of these rules of play, that like the realworld they are more expansive and unpredictable than they really are. At the point that their players have fully grasped the system, learned everything there is to learn, this is the point they realise that it is ultimately a machine, cascading chains of code, a poor diorama.

Sometimes it’s more fun to imagine games without ever actually playing them.

Three

The Shot Tower

I followed the small group of us into the lift and pressed the button for the only other floor aside from this one. The lift doors clicked shut, the floor trembled a little and we began to rise. Every time I stepped in here, I had a premonition that the lift would fail. We might make it two-thirds of the way up before it came to a juddering halt and hung there. Or it might precipitously turn and fall back through the shaft.

But like every other time, nothing happened. Last on, I stepped out first onto the observation deck. The others followed behind. It’s a nice view, offered one person, going up to the window. Another one silently read the informational plaque on the wall next to it. The other two remained by the lift doors and pursued their own, unrelated line of conversation. As invariably as the lift failed to plummet, the shot tower invariably failed to elicit more than a muted reaction from the people brought to see it. After a minute or two standing in the afternoon light, we’d all back into the lift and descend again.

I knew, at least, that here was something strange. I had moved here a few years back into a one-bedroom walkup in this massive complex. The balcony faced north onto the rooftops of identical buildings descending to the valley floor. It was a ten minute walk from here to the other end where the tower was, so often in free afternoons or after work on summer evenings, I will make the trip on my own.

In the previous century it really had been used to produce shot. From the top they poured molten lead through a sieve into its hollow centre, separating into spherical bearings as it fell, solidifying as they landed in the water pool at the bottom. This had been one of the only buildings out this side of the city, alone in the open paddocks, and it had remained standing well after the demand for shot had dropped off.

When the land got sold, covering the whole alotment from the foot of the ridgeline all the way down to the highway, retaining this tower was one of the conditions attached. Which the developer did, and surprisingly, not only did it retain the tower but it wrought this scaffold around it, built the observation deck, fitted it with the only lift in the complex. An act of strange generosity when so many other buildings going up in this city are on the verge of ruin before they’re even completed.

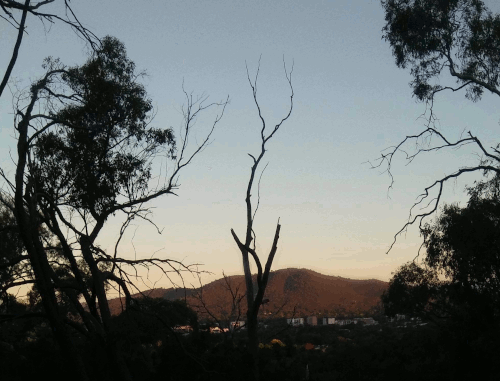

The windows on one side face back uphill towards the rows and rows of apartments. The mountain rising up behind them. The windows on the other side look across the highway to the empty paddocks, which at this time of day are falling into shadow except for where the last sunrays fall between the clouds and ranges. One ray falls through this window and casts a prism of light on the floor, the sieve preserved in a block of resin, turning it shimmering orange.

Despite the large number of dwellings, no-one else is ever up here. The highway, if you follow it for a ten-minutes drive through the underpass, leads back to the rest of the city. Standing here in the waning prism of light, it feels like the far end of the world.

Four

My Trade

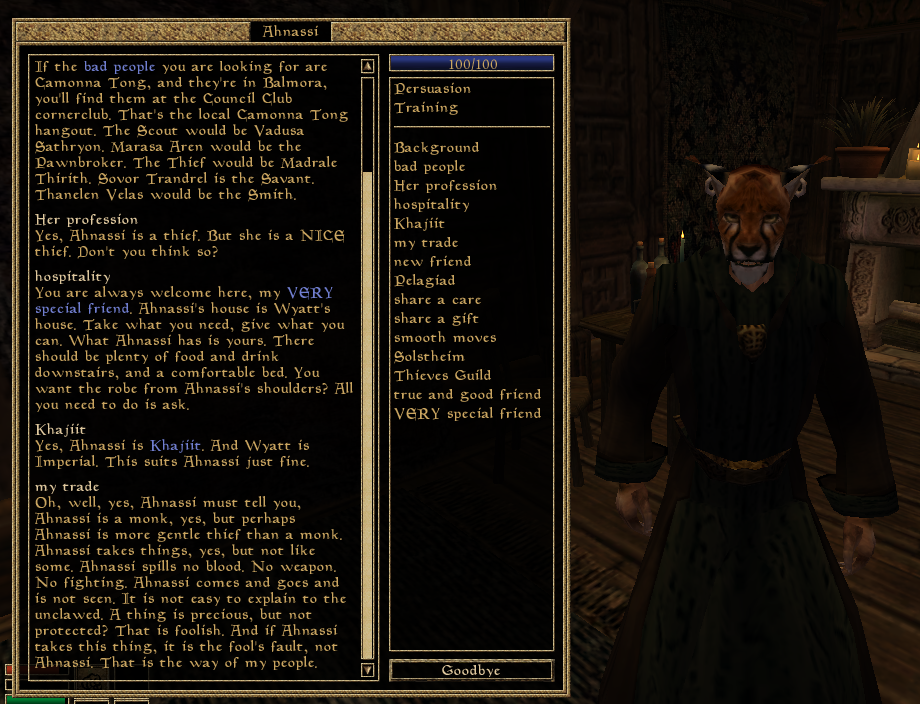

When you open a conversation in Morrowind, it looks like this:

A window dominated by one big text log and in the sidebar a list of commands (admire, bribe, taunt, intimidate) and topics like background, little secret, my trade, rumours. Clicking one of these topics appends a text passage into the text log on the leftside, so that as you click through them you develop an increasingly long conversation history you can refer back to. Some topics will lead to more topics appearing in the sidebar, or alternatively, lead the other character to abruptly break off conversation with you. And based on how well disposed the other character is towards you, their responses will change too. If you’re on good terms they’ll answer most things pretty positively. If they’re neutral they’ll make small talk but evade sensitive topics. If they dislike you, they’ll tell you to go away if they don’t simply try to kill you first.

I love this system. For a game known for its unusual lore and surprising and beautiful art direction, the dialog system is one of the more secretly fascinating bits of Morrowind. This is not to say it’s an entirely effective or realistic way of conveying dialog. Lots of characters share the same responses to topics, meaning you’ll elicit identical responses from wildly different characters. When you encounter someone under the influence of the game’s evil, immortal god Dagoth Ur, most of their dialog will be unhinged and antagonistic, like:

Lord Dagoth has sent the blight to destroy the foreigners, and to chasten those Dunmer who bend to foreign will. Those who oppose Lord Dagoth shall wither and die, while those who join Lord Dagoth shall be healed and strengthened, filled with the power and glory of Red Mountain, and inspired by the dreams of Dagoth Ur.

Or:

You will die, false one. Your flesh will feed us all.

And so on. But then, it’s not too difficult to divert them and elicit the same kind of polite smalltalk you’d get from the other commoners who make up the population, for instance when asking them about an island up north:

A terrible place, I’ve heard. There’s a boat from Khuul, if you have any reason to go.

Because none of this is voice acted, you’ll find the characters often don’t so much respond conversationally. Instead they’ll deliver short monologues on anything ranging from that island to the north, to their professions, to the services available in town. In this vein, I find asking characters about my trade to be a particular source of unintentionally funny dialog. You’ll walk up to some shady looking person on the street and ask them their trade, and get a pretty open admission that they kill people for a living:

I’m an assassin. Killing is my profession. I am discrete, efficient, and reliable. In Morrowind, the assassin’s trade is an ancient and honorable profession, restricted by a rigid code of conduct, and operating strictly within the law. Because I am discreet, I prefer short blades for swift, close-and personal work, while the marksman weapons like throwing stars and throwing knives are more suitable for stealth and surprise. I charge fair prices to train apprentices in the assassin’s skills.

Or they’ll give you an eloquent account of their peasant lives:

I am a pauper, one of the humble smallfolk. I make my way in the world as best I can, laboring in the fields, kitchens, and factories of lords and merchants. When times are good, I live well enough by my own work. When times are hard, I must hope for the charity of the nobles and wealthy merchants.

The effect feels reminiscent of a theatre production, as though the actor is stepping outside the action to deliver a soliloquy. The writers could have just had their characters say “I’m a pauper,” or stuck in some muddled, faux-realistic dialog. I’m grateful for what we got instead. Their responses to other topics read like encyclopedia entries or extracts out of guidebooks, enumerating all the people and places of interest in the region, to a level that seems to exceed simple recall:

All six Redoran councilors, Brara Morvayn, Hlaren Ramoran, Athyn Sarethi, Garisa Llethri, Miner Arobar, and Bolvyn Venim, live in the Manor District. Edwinna Elbert is Mages Guild steward, Percius Mercius is Fighters Guild steward. Old Methal Seran is an eminent Temple priest and scholar. Raesa Pullia is commandant of Fort Buckmoth, but Imsin the Dreamer is the chapter steward. The Redoran Hean is priest of the Imperial cult. Find Goren Andarys, guild steward of the Morag Tong, in the Manor District.

So the dialog in Morrowind does not work in the service of any kind of realism. Compare it to the voice acting and uncanny zooms on characters’ faces in the later games. Dialog in Morrowind is more like looking things up in an encyclopedia. I appreciate the artifice, the lack of realism. Part of this is probably nostalgia for the nineties and early oughts games where these systems had their heyday, but also because are also interesting questions what kinds of affordances we get from these interfaces, what they make possible, what possibilities they close off, beyond just realism.

The few modern games I’ve placed, if they offer branching dialog at all, usually limit it to one or two options. There’ll be a couple specific things you can raise with each character you encounter, usually with voiced responses. Because the game can’t just print reams of text in a window, the writing has to be more concise. It has to try approach something like the way people actually speak. (And even moreso when someone actually has to voice those lines, and when you the player have to then listen to someone voicing those lines.) Not that this turns out to be any more accurate a reflection on how people actually speak, anyway:

Never been to Whiterun before? The Jarl’s palace is something to see. Dragonsreach they call it. Big old dragon skull hanging on the wall.

If most videogames are going to be peculiarly incapable of reflecting the way people actually speak, why foreclose on all the sprawling fun of old roleplaying games like Morrowind. I want long, weird monologues to come back. I want, when a character is prompted about local rumours or gossip, to respond with long rambling passages of text no person would actually have the patience to sit through in reality, if it were verbal. If novelists can get away with sentences that run for pages and pages, then there is no reason for games to limit themselves to this faux-naturalistic two to three line dialog.

More generally, I want to see more novel dialog systems, more experimentation with the form. What about something that sprawls out endlesslessly, that you can become thoroughly lost in, that shifts irreversibly the moment you try to interject. Bring back encylopedic topic lists and textparsing and that system where you can show an item to someone to elicit a unique response. There are, moreover, whole realms of potential in other interactive fiction. What would a dialog system look like that was modelled on Reagan Library’s cycling text extracts that gradually cohere or disintegrate, or on Uncle Roger’s lexia linked together by associative keywords?

Five

Reagan Library

Stuart Moulthrop’s Reagan Library (1999), on its surface, should not have fallen into such a state of deep unplayability. This not-quite-game but also not-quite-cybertext sees you clicking through short, disconnected texts. When you start out, the texts are all jumbled together, missing sections and filled with noisy interference. It is difficult to interpret any coherent narrative in any one of them. Only as you follow links from extract to extract, seeming to move between both different physical spaces like “white cone” and “library,” as well as worldstates, do the fragments slowly begin to cohere. A tracker in the lower right shows you how many times you have landed at a certain extract. Usually by the fourth visit, it will be whole again, and you can read it in its original form. Other extracts, though, seem to disintegrate on subsequent visits, and by the fourth visit will have themselves become ultimately fragmented and incoherent.

As well as the text extracts, at each passage the game shows you a navigable panorama of the space and time you are standing at. All the stories in this game appears to be linked with the same eerie, Mystlike world, an archipelago littered with ruins and monuments, beaches and walls of flame. As an alternative to clicking through the text, you originally had the option of scanning through these panoramas, and clicking across to nearby features, which not only moved you through the virtual space, but propelled you into another worldstate, too. You may click on a nearby monument on an island framed against the blue sky and sea, only to arrive at it in ruins, under a red sky.

This is how the game is supposed to work, anyway, a relatively straightforward combination of pages, javascript to track the game state, and videopanoramas implemented in QuickTime. Only by 2023, the HTML and javascript implementations used by browsers have changed, so that the links don’t work, or possibly are not ferrying you from placetime to placetime as intended. Worse, QuickTime videopanoramas as a format are long dead, long deprecated, and your only option to see them now is to download each individual MOV file and open it in a separate program, Videopanoramas player. This also in effect bars off one of the main ways you used to be able to navigate the game world, meaning that as a result, it is easy to get caught in situations where you are stuck looping through the same few text extracts, unable to go anywhere else, where originally you could have just navigated somewhere else in view.

Being, at its core, a series of linked webpages, it is still possible to experience Reagan Library in a degraded form, and it remains well worth doing so. The game eerily probes death and memory loss and ruin and decomposition, and in a way, it seems ironically fitting that a game exploring these themes has itself been obsoleted by shifting technology over the past two decades.

Six

Department Store Dream

I was in a shopping mall, a department store, shopping for lipstick and dresses. The stores were open, but it was a borderline kind of day and hour where they were mostly empty, and felt as though they might shut soon. Everything was wood and timber, even the store shelves, and spaced out so that the department store I’d wandered into seemed to cover acres and acres. Warm sunlight streamed through the big bay windows. For all that I recall this nostalgically now, at the time things felt a little uneasy, as though there was still a threat somewhere in all that soft light and warm timber.